Derek Holliday, Yphtach Lelkes, and Sean J. Westwood

Did Donald Trump’s indictment increase support for democratic norm violations and political violence? Political commentators have indicated concern that pursuing criminal charges against the former president may inflame antipathy between partisans. Using survey data covering the periods before and after Trump’s indictment, we show no lasting, significant changes in the attitudes of partisans. Any differences in attitudes before and after the indictment quickly dissipated to pre-indictment levels within a few days. Our results have positive implications for the health of our democracy, suggesting politicians can be held accountable for criminal activity without widespread threat of retaliation from supporters.

Data

Our data come from a daily survey of Americans’ political attitudes. In total, we analyze the responses of 29,725 respondents from September 16, 2022 through June 29, 2023, which includes 1,763 responses gathered on or after June 14, the date of Trump’s indictment. All respondents in our data identify as either a Democrat or Republican and pass a simple attention check. All respondents are asked to rate their agreement with a series of five statements related to democratic norm violations and four statements related to political violence on a five-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, which we recode individually as a binary measure of agree/don’t agree. We list the democratic norm items in full below:

1. Reduce outparty polling stations: Do you agree or disagree: (inparty) should reduce the number of polling stations in areas that typically support (outparty).2. More loyal to party than election rules and constitution: Do you agree or disagree with the following: When a (inparty) candidate questions the outcome of an election other (inparty) should be more loyal to the (inparty) party than to election rules and the constitution.3. Ignore outparty court decisions: Do you agree or disagree: (inparty) elected officials should sometimes consider ignoring court decisions when the judges who issued those decisions were appointed by (outparty) presidents. 4. President should circumvent congress: Do you agree or disagree: If a (inparty) president can’t get cooperation from (outparty) members of congress to pass new laws, the (inparty) president should circumvent Congress and issue executive orders on their own to accomplish their priorities.5. Censor partisan media: Do you agree or disagree with the following: The government should be able to censor media sources that spend more time attacking (inparty) than (outparty).

Additionally, respondents are asked several questions related to feelings of warmth toward members of the same party and members of the opposite party, with responses on a 0-100 scale.

Method

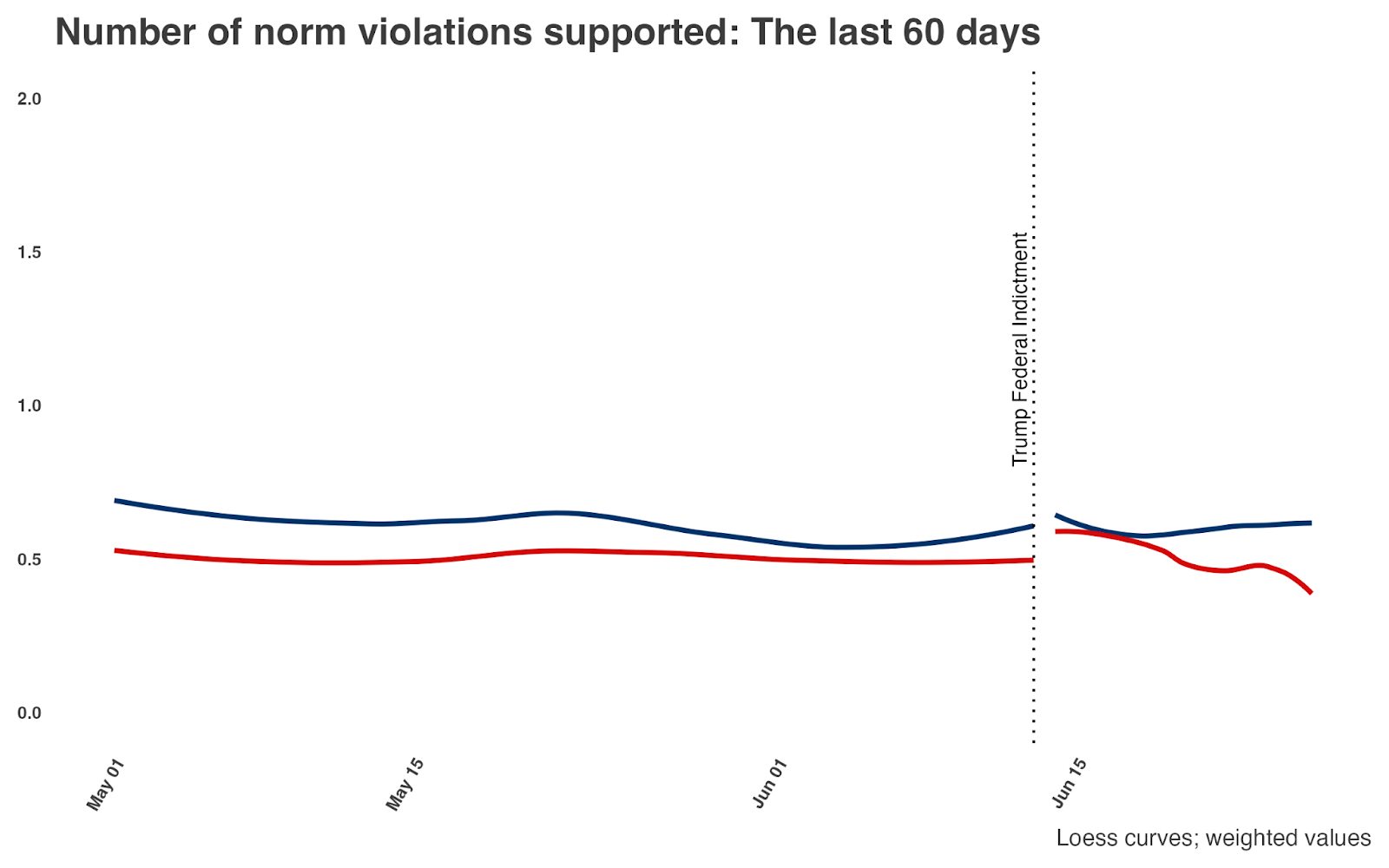

We implement an interrupted time series design to measure changes in attitudes among partisans pre- and post-indictment. Specifically, we assume independent trends in support for democratic norm violations, political violence, and affective polarization before and after Trump’s indictment. Over-time trends, however, can be linear or non-linear. In our preferred specification (shown in the graphical results), we fitted smoothed (loess) curves over the pre- and post-indictment periods. This allows for the trend to more closely follow short-term increases and decreases in our variables of interest. In the appendix, we fit linear models to the data, which largely cohere with the models we present below. All analyses are weighted to reflect the national population.

Results

First, we analyze changes in support for political violence between May 1 and July 26, 2023, by party. Specifically, we estimate the proportion of respondents supportive of assaulting an out-party member. We find there is no meaningful change in support for violence after Trump’s indictment. Such support remains incredibly rare (around 3 percent) among both Democrats and Republicans.

Support for political violence, of course, represents one of the more extreme attitudinal positions respondents can take. How did support for democratic norms change after Trump’s indictment? We measure support for democratic norm violations as an index, summing over the five norms in our survey and reporting the average number of norm violations supported by partisans. Here, we find there is a very small increase in support for norm violations among Republicans immediately after the indictment of around one seventh of a single additional norm violation, although Republicans still do not become more supportive than Democrats.* Additionally, this small increase in support vanishes extremely quickly, returning to baseline levels just a week after the indictment. This suggests attitudes toward democracy are largely robust to Trump’s legal battles.

* We caution, however, against overstating the significance of apparent differences in loess curves that emerge from daily variations in attitudes. While our sample is large in aggregate, there is randomness in the representativeness of respondents completing the survey on any given day. While we omit confidence intervals in our graphics to more clearly show the trend lines themselves, we note here many of the apparent effects in the days immediately following Trump’s indictment are highly uncertain.

We also aim to capture more generalized changes in partisan feelings toward both in-party and out-party members. We may expect feelings toward rival partisans to grow colder after Trump’s indictment, which could further chill partisan relations in the country. We test this possibility by tracking the level of affective polarization by party pre- and post-indictment. Affective polarization is defined as the difference in feelings of in- and out-party warmth on 0-100 feeling thermometers.

Similar to trends in support for democratic norm violations, we see a small uptick in affective polarization among Republicans after Trump’s indictment, but this small increase rapidly falls back to pre-indictment levels. At present, partisans are again at parity with regard to affective polarization.

Surprisingly, however, this temporary increase in affective polarization was not driven by out-party antipathy. As we show below, it was in-party affect that increased (among both parties) after the indictment. Among Republicans, this affective bonus toward fellow Republicans dissipated quickly back to pre-indictment levels, which we interpret as a sort of “rally around the flag” effect. Democrats, on the other hand, showed a slightly more temporally robust increase in warmth toward co-partisans. This may be interpreted as an expression of self-congratulation for finally bringing criminal charges against Trump.

Conclusion

Trump’s indictment did not seem to change Americans’ attitudes about political violence, democracy, or members of the opposing party. If any changes did occur, they were both minor and fleeting. We take this evidence as hopeful for the prospects of holding public officials, even of high importance to partisans, accountable for their actions. While we cannot rule out small, radical groups retaliating for legal prosecution of Donald Trump, it is certainly not the case that broader American attitudes changed in the wake of his indictment.

Appendix

For all models in the main text, we make minimal parametric assumptions across all attitudes by fitting loess curves to the pre- and post-indictment periods. This makes the curve sensitive to local minima and maxima in the data, as the slope of the curve is weighted to be responsive to local deviations.

In addition to the loess models shown above, we fit a series of corresponding linear specifications and report our results below. For each dependent variable, we estimate two specifications. First, we regress our dependent variable on a binary indicator for pre- or post indictment, a dummy for Republican party identification, and an interaction between the two. The quantity of substantive interest is the coefficient on the interaction term, indicating whether average Republican attitudes changed post-indictment.

For our second specification, we split the post-period into the first and second weeks post-indictment in order to determine shorter-term trends in the post-indictment period. The quantity of interest is again the coefficient for the interaction term. If changes in Republican attitudes are greatest in the week immediately following Trump’s indictment, we’d expect the coefficient on the interaction between week 1 and Republican to be significant and the interaction for week 2 to be insignificant.

Table: Support for Assault

| OLS Pre-Post | OLS Weeks | |

| (Intercept) | 0.034*** | 0.034*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Post Indictment | 0.002 | |

| (0.006) | ||

| Republican | -0.010*** | -0.010*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Post x Republican | 0.004 | |

| (0.008) | ||

| Week 1 Post-Indictment | 0.005 | |

| (0.008) | ||

| Week 2 Post-Indictment | -0.001 | |

| (0.007) | ||

| Week 1 x Republican | 0.004 | |

| (0.012) | ||

| Week 2 x Republican | 0.005 | |

| (0.011) | ||

| :———————– | ————-: | ———-: |

| Num.Obs. | 29725 | 29725 |

| R2 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Log.Lik. | 8949.595 | 8949.794 |

Table: Support for Democratic Norm Violations

| OLS Pre-Post | OLS Weeks | |

| (Intercept) | 1.016*** | 1.016*** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Post Indictment | -0.093* | |

| (0.041) | ||

| Republican | -0.154*** | -0.154*** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| Post x Republican | 0.165** | |

| (0.062) | ||

| Week 1 Post-Indictment | -0.119* | |

| (0.060) | ||

| Week 2 Post-Indictment | -0.072 | |

| (0.055) | ||

| Week 1 x Republican | 0.195* | |

| (0.090) | ||

| Week 2 x Republican | 0.141 | |

| (0.083) | ||

| :———————– | ————-: | ———–: |

| Num.Obs. | 25915 | 25915 |

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Log.Lik. | -43884.794 | -43884.612 |

Table: Affective Polarization and In-Party Warmth

| Affpol Pre-Post | Affpol Weeks | In-Party Pre-Post | In-Party Weeks | |

| (Intercept) | 54.093*** | 54.093*** | 75.692*** | 75.692*** |

| (0.259) | (0.259) | (0.169) | (0.169) | |

| Post Indictment | -1.620 | -0.267 | ||

| (1.047) | (0.682) | |||

| Republican | -1.680*** | -1.680*** | -1.781*** | -1.781*** |

| (0.385) | (0.385) | (0.250) | (0.250) | |

| Post x Republican | 0.662 | 0.024 | ||

| (1.584) | (1.031) | |||

| Week 1 Post-Indictment | -0.188 | 1.189 | ||

| (1.524) | (0.993) | |||

| Week 2 Post-Indictment | -2.819* | -1.486 | ||

| (1.399) | (0.911) | |||

| Week 1 x Republican | -1.528 | -1.574 | ||

| (2.298) | (1.493) | |||

| Week 2 x Republican | 2.515 | 1.367 | ||

| (2.126) | (1.385) | |||

| :———————– | —————-: | ————-: | ——————: | —————: |

| Num.Obs. | 29574 | 29574 | 29680 | 29680 |

| R2 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Log.Lik. | -145893.953 | -145892.932 | -133700.579 | -133698.529 |

Note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Note: Estimated with survey weights